Charles Edwin Jones was the original prospector of this find, but a poet and medical student from South Australia named Derham (Dorrie) Longford Doolette made the significant find. He was lured west by the rich discoveries made at Coolgardie. He managed several mines and also paid prospectors to go out searching. Many of his ventures were successful. Several were listed on the London market through his father.

In 1909, while he was in Mount Magnet managing the St George mine, he formed a partnership with Vincent Shallcross. The two men backed Charlie Jones, a mine sampler, to prospect in Yilgarn.

Doolette became interested in this area five or six years prior when he was travelling in the Golden Valley. It was close to where Colreavy and Huggins pegged leases in 1887. Colreavy and Huggins claimed the Government rewarded of £1,000 for discovering the first goldfield east of Perth with their partners, Greaves, Payne, and Anstey.

Doolette noticed that the Golden Valley road intersected a narrow belt of talcose and chloritic schists, which looked like a promising area to prospect. On a later search with Vere Poulett-Harris and Harry Hoffman he discovered a belt of gold-bearing schists, 18 kilometres north-west of Southern Cross and extending 27 kilometres towards Golden Valley. Two of the mines that developed from the find were the Corinthian and Corinthian North.

Charlie Jones's instructions were to examine the Corinthian belt and some adjacent areas. He was to receive one-eighth of anything found, with Doolette and Shallcross sharing the remainder. It was not long before he came across some prominent outcrops and quartz floaters carrying gold prospects in country thick with scrub and tea-trees. Jones applied for three leases and then returned to Mount Magnet as the scanty local water supply had run out.

After receiving this news, Doolette and Shallcross visited the leases. Shallcross was not impressed with what he saw as he thought the deposits were only superficial. He sold his share to Doolette for £1,000. Shallcross was to regret this hasty action and later paid dearly to become a shareholder again: Jones sold him half of his stock, one-sixteenth, for £10,000.

The first shaft was sunk to 30 metres through rich ore averaging 250 grams. When a crosscut was put through, it gave values of 620 grams to the tonne. The ore was bagged and carted by team to Southern Cross and then railed to Kalgoorlie where it was treated by the Gold Recovery Co.

Some of these were Steve Eastwood, Jerry McAuliffe, Tom Brimage, Warden Finnerty, Charles de Rose, Bob Hair, Charles Cutbush, J. Fimister, and seventy-year-old Paddy Hannan, the discoverer of Kalgoorlie. Hannan had retired and was living with relatives in Brunswick, Victoria, when he heard of the Bullfinch strike. He travelled west again and joined his old mates to prospect the district. His search was unsuccessful, so he returned to the east where he lived for the remaining twelve years of his life.

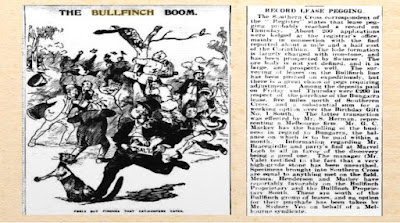

The rough track between Southern Cross and Bullfinch was full of motor cars, buggies, spring carts, wagons, and drays, and a considerable number of men 'humped Matilda'. These were the early days of the motor car, and a newspaper advertisement in a golfields' newspaper read:

'Bullfinch Rush. Easy going. Lapharr's Darracq Motor Car. The best on the Fields and capable of carrying four at a time or five with your best girl on your knee, is open to hire at ten pounds a day. Apply Linton 's Auction Mart, Southern Cross.'

The few men, including Doolette, who owned a motor car reached the scene of a reported strike before the other prospectors. Many felt they had an unfair advantage.

On the road to Bullfinch, 1910

https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/45137979/3379669

Charlie Jones noticed a stranger wandering around over the rich, soft ore that had broken out on the surface of the mine after heavy rain. Jones and other onlookers were puzzled by the man's behaviour as he walked about, paddling in some of the pools of water. As he did not bend down to pick up anything, they decided that he must be crazy. Jones investigated further. He discovered that the thick, auriferous mud that clung to his boots contained many grams of gold. The stranger had washed the mud off his boots into pools of water to collect after they dried out. The man was promptly ordered off the lease.

https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/211800486

Doolette visited London and held a banquet where he presented each guest with a little model bullfinch made of solid gold. There was no trouble in getting investors to buy shares in the mine. During 1910, 340,854 grams were produced from 1027 tonnes of ore. These values tapered off but in 1912 were still high enough to warrant the erection of a twenty-head battery and other plants to treat the ore on site. In 1920 the grade of ore declined. In the second half of the year, the mine ran at a loss, and it was closed in May 1921.

In 1922 the district was thrown open for wheat farming, saving Bullfinch from becoming a ghost town. Some gold mining continued in the area. After the Second World War, another mining boom occurred at Bullfinch when Western Mining took over the Copperhead leases. They set up a subsidiary company, the Great Western Consolidated, to handle its interest in the Yilgarn area.

By 1950 the Copperhead mine was employing 130 men, and the company had built for them a new town with all modern amenities. The mine became the second most significant mining venture in the State, after Big Bell. Plant and equipment cost £2 million, and the plant treated ore from the Copperhead leases and other ore from the district. During 1952 it was handling 45 000 tonnes a month.

Mining activity began to decline in 1960 and on 24 May 1963, the Copperhead ceased production. The residents of Bullfinch then had to find work elsewhere. The mining equipment and the buildings in the town were put up for sale. Bullfinch is no longer a mining town and a few inhabitants still live in the townsite, saving it from ghost town status. It is now clinging on as a small centre of one of the State's other primary industries, wheat farming.

First published in Norma King's "Colourful Tales of the Western Australian Goldfields" in 1980 https://www.yilgarn.wa.gov.au/visitors/attractions/bullfinch.aspx

No comments:

Post a Comment